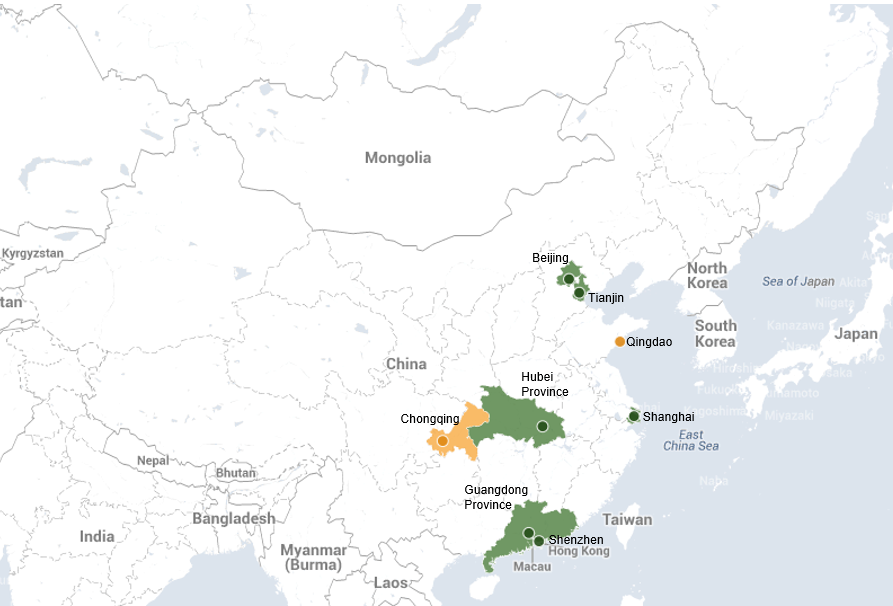

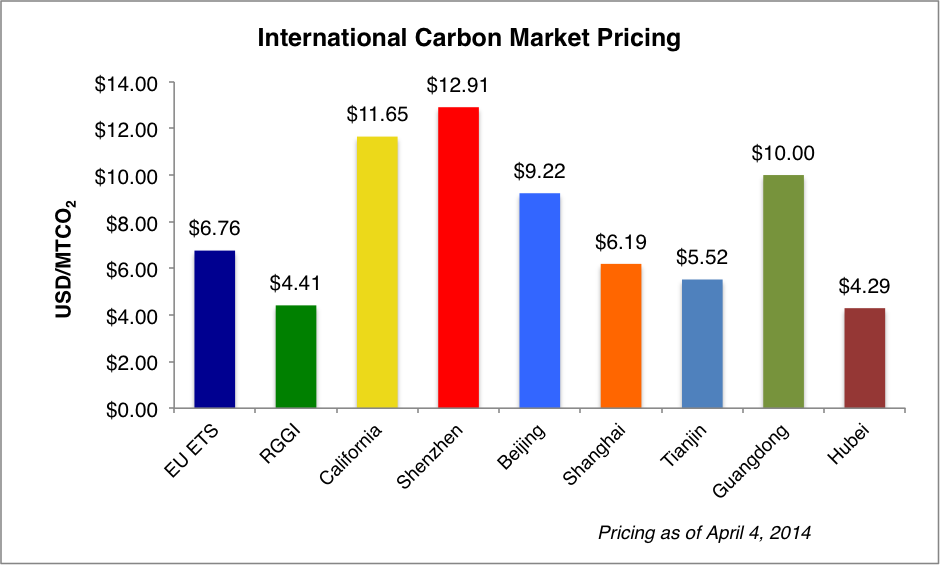

Last week, Hubei Province became the sixth jurisdiction in China to launch a pilot carbon emissions trading program, joining Shenzhen, Shanghai, Beijing, Tianjin, and Guangdong Province. In the coming months, two additional programs will be introduced in Chongqing and Qingdao. In total, the eight pilot programs will cover an estimated one billion metric tons of carbon dioxide (MTCO2), second only to the European Union’s Emissions Trading System. The pilot trading programs are part of the strategy laid out in China’s 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-2015) to reduce carbon intensity (CO2 emissions per unit of GDP) by 40-45 percent from 2005 levels by 2020.

As the world’s largest energy consumer and emitter of carbon dioxide, China’s efforts to rein in emissions are significant at both the global and national level. In addition to the carbon trading pilots, China recently announced measures to limit coal to 65 percent of primary domestic energy consumption by 2017, down from 69 percent in 2011, while also banning new coal generation in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou.

To meet its 2020 emissions goal, China is expected to introduce a timeline for a national carbon emissions trading program in its 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020). The plan, in addition to supporting China’s domestic targets, could also complement broader goals that will be outlined in a new post-2020 international climate agreement that countries will formulate in late 2015. In February, the United States and China pledged to strengthen bilateral cooperation in developing their respective post-2020 climate commitments. In the lead-up to 2015, China’s pilot trading programs will present policymakers with a set of unique policy options and data points to use in crafting a national program. So, it is worth exploring some key elements.