Introduction

There is growing momentum in the United States toward a more robust response to climate change. States, cities, and companies across the country are stepping up their efforts, driven both by the rising toll of extreme weather and other climate impacts and by the economic dividends of a clean energy transition. A growing majority of Americans favor stronger climate efforts, and debate is again underway in Washington on comprehensive long-term solutions.

This report offers policy-makers and stakeholders one vision for aligning the U.S. economy with the historic imperative of ensuring future generations a safe and stable climate. It is based on extensive consultations with leading companies across key economic sectors—companies that recognize the irrefutable risks and realities of climate change and are committed to working with policy-makers, customers and investors, and other stakeholders to develop and implement strategies that will progressively decarbonize the U.S. economy.

No single volume can hope to enumerate all the facets of a comprehensive U.S. climate strategy. Rather, the objective here is to outline the broad contours of an effective long-term strategy and to identify a set of key actions that should be taken over the coming decade to put the United States firmly on the path to decarbonization.

Getting to Zero: A U.S. Climate Agenda emerges from the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions’ (C2ES’s) Climate Innovation 2050 initiative, which provides an ongoing forum for companies to examine decarbonization challenges and solutions. It builds on Pathways to 2050: Alternative Scenarios for Decarbonizing the U.S. Economy, our earlier report based on a year-long collaboration with companies and experts envisioning three alternative pathways to substantially decarbonize the economy by 2050.

Our agenda is grounded in the firm belief that unchecked climate change poses grave risks to America’s wellbeing—and that an effective and durable response can not only reduce those risks but also help to grow

and sustain our nation’s prosperity.

Toward those ends, this report:

- Examines the fundamental nature of our decarbonization challenge and recommends overarching objectives for a U.S. decarbonization strategy

- Outlines the core elements of a long-term climate policy framework, including policies to price carbon, accelerate innovation, mobilize finance, and ensure a just transition

- Outlines priority federal, state and local policies to help decarbonize the power, transportation, industry, buildings, oil and gas, and land-use sectors

- Highlights technology pathways with significant potential across multiple sectors

- Recommends ways that companies can demonstrate stronger leadership in meeting the decarbonization challenge

- Throughout the report, we offer snapshot visions of the future this agenda could help to produce.

The diverse array of policy approaches recommended here are intended to work in concert to address the many facets of the overall decarbonization challenge. While a robust carbon price will send a broad signal across the economy to reduce emissions, companion policies from the federal to the local level will help mobilize private investment, ensure that the necessary technologies and infrastructure are in place, and provide targeted incentives to both companies and consumers to accelerate the transition. The nature of these companion policies varies across sectors, and their precise mix and timing will depend in part on how quickly a meaningful carbon price is put in place. But for any given sector, it is the totality of these approaches working together, rather than any single policy, that will produce the necessary results.

Through Climate Innovation 2050, C2ES will continue working with companies on a sector-by-sector basis to elaborate and refine these strategies. It is our sincere hope that these initial recommendations benefit policy-makers and stakeholders alike and serve to inform and stimulate this vital national debate. We look forward to working with partners in all spheres to mobilize a U.S. climate effort commensurate with this historic challenge.

II. The Decarbonization Challenge

II. The Decarbonization Challenge

Decarbonizing the U.S. and global economies represents perhaps the most ambitious and complex societal transformation ever undertaken. A successful strategy must be grounded in a firm understanding of the strong scientific rationale for this mission; the scale, scope, and urgency of this transformation; and the fundamental features of the decarbonization challenge.

What Science Tells Us

For more than three decades, the United States has worked in partnership with other countries to advance scientific understanding of climate change. The result is a large and strong body of evidence and analysis documenting the worsening physical, economic, and social effects of human-induced climate change. This broad consensus is reflected in the series of assessments undertaken since 1990 by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and in separate analyses by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences and other independent scientific bodies.

Two recent reports outline the potential impacts of climate change on a global scale and in the United States. The IPCC’s special report Global Warming of 1.5°C, adopted by the United States and other governments in October 2018, warns of wide-scale and, in some cases, catastrophic or irreversible impacts on ecosystems, economies, and human populations if average warming exceeds 1.5 degrees C. The Fourth National Climate Assessment, published by the U.S. government in November 2018, exhaustively details the expected impacts of climate change on the United States and projects hundreds of billions of dollars in further economic losses.

Guided by the overwhelming scientific consensus, the United States and other governments set out in the Paris Agreement a set of collective goals to limit the impacts of climate change. These goals include keeping the rise in global average temperature well below 2 degrees C above pre-industrial levels (and pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5 degrees C), achieving peak global emissions and reducing them as quickly as possible, and achieving a balance between greenhouse gas emissions and removals (i.e., net-zero emissions) in the second half of this century. The IPCC’s subsequent 1.5°C analysis underscores the importance of achieving carbon neutrality no later than 2050.

Key Elements of Decarbonization

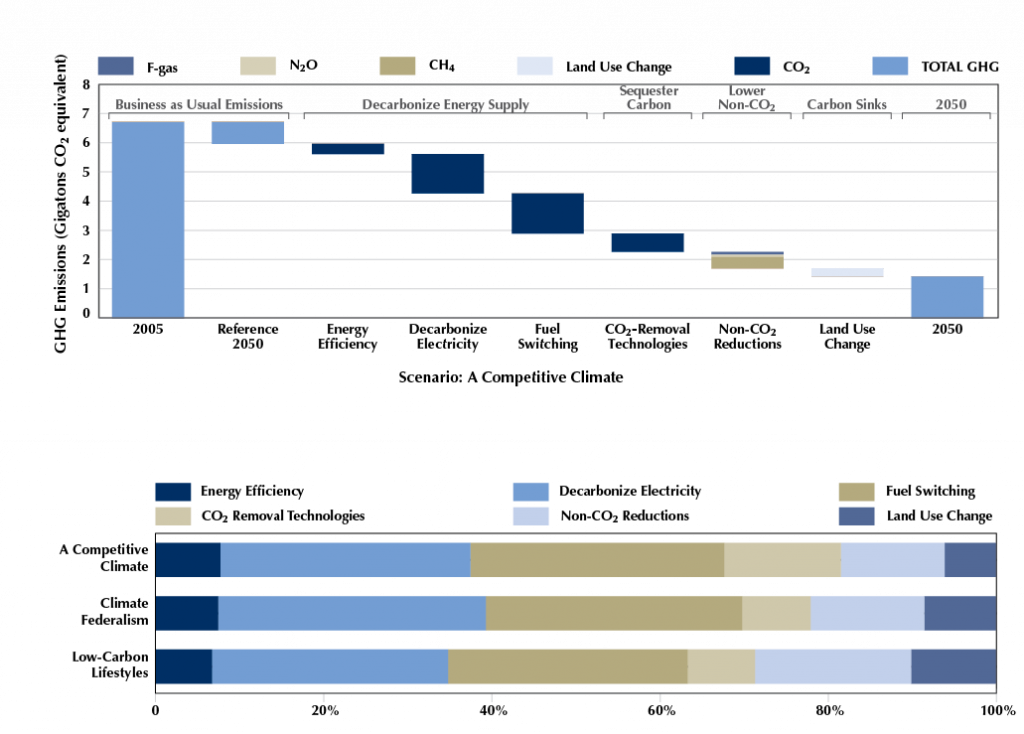

Consistent with a broad range of previous analyses, the scenario exercise described in our Pathways to 2050 report demonstrated that any pathway to decarbonization entails fundamental shifts in the way we power our homes and economies, produce goods, deliver services, transport people and goods, and manage our lands. Figure 1 illustrates how these shifts are reflected in the Pathways report’s three scenarios. They include:

- Increasing energy efficiency across the economy

- Decarbonizing the power supply

- Switching to electricity and other zero- and

low-carbon fuels in transportation, buildings,

and industry - Increasing sequestration of carbon dioxide (CO2) through the use of carbon capture technologies

- Reducing emissions of non-CO2 climate pollutants including methane, nitrous oxide, fluorinated gases and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs)

- Increasing sequestration of CO2 by enhancing natural carbon sinks, including forests and agricultural soils.

Major decarbonization analyses consistently indicate that each of these elements must play an important role, although as Figure 1 suggests, the relative contributions of each can vary depending on a host of factors. For instance, how heavily society must rely on different forms of carbon sequestration to achieve carbon neutrality will depend on our success in reducing emissions.

An Innovation Challenge

Our successes thus far in decarbonizing the U.S. economy are largely the result of technological innovation. Prime examples include the rapid growth of renewable energy, as well as the role of new drilling technologies in enabling the substitution of natural gas for coal in electricity generation, the largest source of the 13 percent reduction in U.S. emissions achieved since 2005. Fully decarbonizing the economy will similarly require innovation across all key sectors, at a pace and on a scale without precedent.

Driving this innovation is the responsibility of both the public and private sectors and requires strong partnership between the two. The drilling technologies that led to the U.S. natural gas boom were nurtured by federal research and policies, better enabling private industry to bring them to scale. The same is true for many renewable energy technologies. A U.S. climate strategy must dedicate the public resources and foster the public-private collaboration needed to accelerate innovation across a wide of range of decarbonization technologies.

However, while technological innovation can greatly facilitate decarbonization, innovation alone is not enough. Without adequate incentives and policies, many carbon-saving technologies are not being widely deployed; some existing energy efficiency technologies are a prime example. In addition, rapidly emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence or autonomous vehicles could, depending on how they evolve, either contribute to or deter decarbonization. Ultimately, translating innovation into carbon neutrality is contingent on sufficient policy drivers.

All Must Do Their Part

The breadth and scale of the decarbonization challenge necessitate an all-in effort. We must look to governments at all levels to set goals and standards, provide market signals and incentives, invest public resources, and maintain a level playing field. We must look to the private sector to mobilize capital, apply its expertise and entrepreneurial energies, accelerate both technology and business model innovation, collaborate across and between sectors, and support enabling policies. We must look to investors to steer finance toward low- and zero-carbon technologies and business models. And we must look to the public at large to express, as citizens and consumers, a preference for the policies and products that can deliver a decarbonized future.

Timing Is Critical

For many years, experts and advocates encouraged “early action” to address climate change, believing it would produce valuable lessons and reduce long-term costs. That time is now past. While some important progress has been made, we are now far behind the curve, and we must act urgently to make up for lost time. The IPCC’s 1.5 degrees C report makes clear that decisive action is critical by 2030 to avoid the worst potential impacts of warming.

Urgent action is required not only because the risks of catastrophic climate change are growing, but also because the actions needed to reduce them will in many cases not produce instantaneous results. Even with substantial new investment in research and development, new technologies can take decades to emerge and mature. Where the necessary technologies already exist, it takes time to build the infrastructure to deploy them at scale. So, too, does determining the right mix of policy mandates and incentives.

Achieving decarbonization without causing undue economic harm requires close attention to other temporal dimensions as well. Each sector presents its own challenges, whether the long-term investment cycles of the power and industrial sectors or the natural turnover rates for buildings, vehicles, and major appliances. A climate strategy will be most successful and least costly to the degree that it can align with, capitalize on, and judiciously accelerate these economic rhythms.

The Benefits Are Many

The strongest rationale for a decarbonization strategy may be the avoidance of escalating harms, including the costly impacts of extreme weather, floods, and wildfires on life, property, and commerce; the dire health consequences of heat waves and more rampant infectious disease; and the national security implications of instability and conflict driven by worsening drought, food shortages, and refugee flows.

Beyond avoiding such harms, decarbonization can yield enormous co-benefits, especially in driving economic growth and enhancing U.S. competitiveness. Natural gas, renewables, and energy efficiency—all helping to decarbonize the U.S. power supply—accounted in 2017 for more than half of the 6.5 million jobs in the U.S. energy industry. As other countries undertake their own energy transitions, U.S. firms can leverage their own innovative technologies and know-how into leading positions in the soaring global clean energy market.

Figure 1: Key elements of decarbonization

III. Strategic Objectives

III. Strategic Objectives

An effective decarbonization strategy must be not only appropriately scaled but also durable, which requires that it rest on a broad political consensus. For such a consensus to emerge and be sustained, the strategy must consider and address a combination of important climate and non-climate objectives. Its overarching objectives should be the following:

Carbon Neutrality. There is broad recognition within the scientific community, and among governments, that averting the worst potential consequences of climate change requires achieving a net balance between greenhouse gas emissions and withdrawals within the coming decades. In line with the latest findings of the IPCC, the United States should aim to achieve net-zero emissions no later than 2050 (see Box 1, Carbon Neutrality vs. Net-Zero Emissions).

Global Leadership. Climate change is an inherently global challenge that cannot be met by the United States alone. The Paris Agreement marks a fundamental shift in the global climate effort, committing all countries to undertake progressively stronger efforts and providing mechanisms to verify whether they are fulfilling their promises. A strong U.S. climate strategy will reestablish the United States as a global leader on climate, better enabling it to press other countries to contribute their fair share to the global effort.

Technology Inclusiveness. Achieving carbon neutrality will require the mobilization of a broad array of low- and zero-carbon technologies. Given the scale and urgency of the challenge, we cannot afford to exclude potentially viable solutions. A U.S. strategy should take full advantage of the range of available and emerging technologies, including renewable energy, nuclear power, and carbon capture. It also should seek to ensure that emerging technologies not obviously climate-related, such as artificial intelligence and autonomous vehicles, develop in ways that contribute to, rather than detract from, decarbonization.

Cost-Effectiveness. Decarbonizing the economy requires a significant shift in the allocation of public and private capital—investments that will reap significant long-term dividends in the form of economic growth and avoided climate damages. These economic benefits, as well as public support for climate action, can be maximized by making sure our decarbonization strategy is as cost-effective as possible. It should to the degree practical align with natural capital cycles and stock turnover. Wherever feasible, it should rely on market-based approaches to reduce emissions at the lowest possible cost.

U.S. Competitiveness. The United States should seek to fully capture the competitive benefits of its decarbonization efforts. The public and private sectors should work closely to maximize opportunities for the export of U.S. technologies, products, and expertise. A U.S. strategy must also preserve competitiveness by providing appropriate safeguards for energy-intensive trade-exposed industries.

Equity. A U.S. climate strategy must strive to benefit all Americans and leave none worse off. It should ensure that the costs of decarbonizing do not fall disproportionately on those least able to absorb them. It should take account of the relative circumstances of different states and regions and treat them equitably. It should also help workers and communities once or still dependent on high-carbon industries to ensure them a place in a decarbonizing economy.

Resilience. Fully addressing climate change requires both mitigation (actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions) and adaptation (actions to strengthen our resilience to the impacts of climate change that cannot be avoided). A decarbonization strategy, by definition, focuses primarily on mitigation, but it should also maximize opportunities for actions that can deliver both mitigation and adaptation benefits, such as deploying microgrids and upgrading the built environment.

Adaptability. No strategy of the scale and duration that we are urging can be fully formed from the outset. On multiple fronts—policy, technology, finance—success will hinge heavily on learning by doing. Unforeseen circumstances and unintended consequences may arise at any stage. A U.S. climate strategy should set clear milestones but be designed to adapt based on experience and evolving circumstances. It should include mechanisms to periodically assess progress, evaluate new information, and, when warranted, adjust policies and priorities.

Predictability. While remaining adaptable, a U.S. decarbonization strategy must outline clear goals and pathways that provide sufficient predictability and stability to guide long-term investment decisions. It also should be designed to facilitate a smooth transition from existing to new policy structures in order to minimize regulatory confusion and overlap without compromising environmental integrity and benefits.

Box 1: Carbon Neutrality vs. Net-Zero Emissions

This agenda aims for the decarbonization of the U.S. economy. The goal is “carbon neutrality” or “net-zero emissions”—terms we use interchangeably here. Both describe a state in which greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere are balanced by greenhouse gas withdrawals from the atmosphere. Some activities or sectors may continue emitting greenhouse gases, provided these emissions are fully offset by withdrawals. These withdrawals (or “negative emissions”) can be achieved either by increasing carbon sequestration by plants and soils (sometimes referred to as nature-based solutions) or through direct air capture, technologies that absorb carbon from the atmosphere.

Economy-wide Emissions at a Glance

Current and cumulative emissions. The United States currently produces about 14 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, second only to China. The climate change occurring today is the result of cumulative emissions over time, however, and the United States remains by far the world’s largest cumulative emitter.

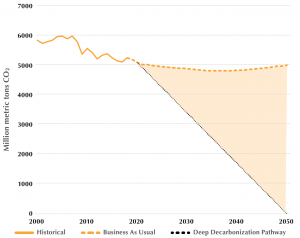

Trends. U.S. emissions have declined by 13 percent since 2005. Under business as usual (no new policies), energy-related CO2 emissions are projected to remain relatively level through 2050.

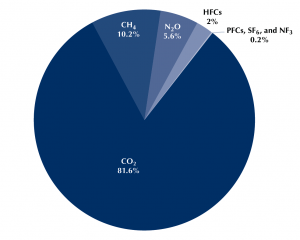

Principal greenhouse gases. CO2 represents 82 percent of total U.S. emissions, with fossil fuel combustion the largest source. Other gases including methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases (i.e., HFCs, perfluorocarbons , sulfur hexafluoride, and nitrogen trifluoride) also contribute to atmospheric warming. While these “short-lived” gases do not remain in the atmosphere as long as CO2, they are more potent. For example, one ton of methane creates as much warming as 25 tons of CO2 over a 100-year time period.

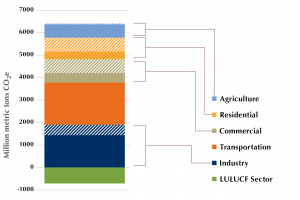

Emissions by sector. About 30 percent of U.S. emissions result from the generation of electricity. A sector’s total emissions include both its direct emissions and the “indirect” emissions associated with the electricity it consumes. Looking at both direct and indirect emissions, the largest-emitting sectors are buildings (31 percent), industry (30 percent), transportation (29 percent), and agriculture (10 percent).

Negative emissions through land use. U.S. emissions are offset somewhat by the natural sequestration of carbon in soils and vegetation. These “negative emissions” currently offset about 11 percent of U.S. emissions.

U.S. emissions by greenhouse gas, 2017

U.S. emissions by sector, 2017

Energy-related CO2 emissions, 1990-2050