Costs

Costs to reduce short-lived climate pollutants can vary depending on the source of the pollutant and the available technologies to reduce those emissions. Typically, costs will be lower for reductions achieved through efficiency improvements or using substitutes that emit fewer climate pollutants—these options may even generate a net savings. For example, achieving energy efficiency in buildings and appliances costs less than reducing the carbon intensity of power plants, where capital-intensive technologies that need to be installed may take more time.

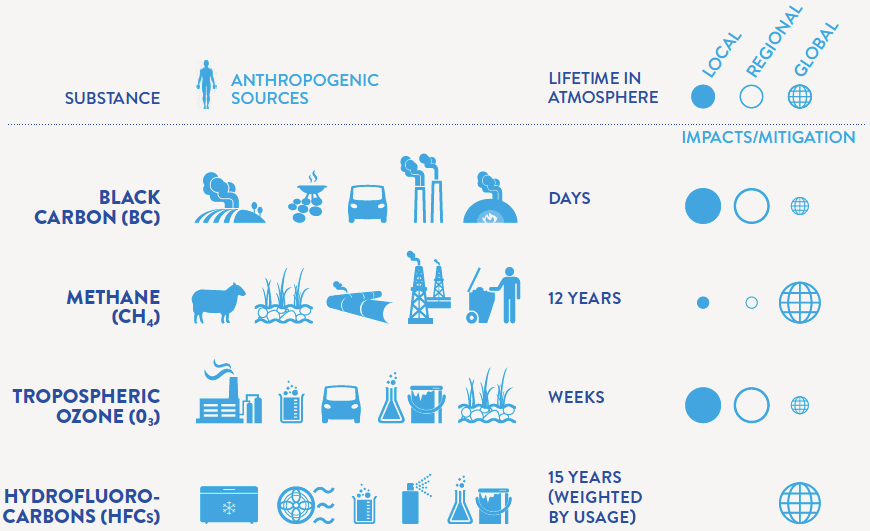

In addition, emissions from a fixed, identifiable source present more cost-effective emissions reduction options than other diffuse emissions sources. For example, it is easier to address fugitive emissions from a single building than emissions from mobile, fossil-fuel burning cars and trucks. Actions taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions elsewhere, such as reduced biomass burning, can also help reduce SLCPs and other high global warming gases. Cost-benefit analyses that take into account the human health impacts of pollutants can also make mitigation strategies more appealing Policy Actions on SLCP Mitigation.

International Efforts

The Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC) is a cooperative public-private initiative that promotes national and international action but establishes no legal obligations or authorities. Formed in 2012, the coalition includes the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and other governments around the world, united to address short-lived climate pollutants and to deliver action and benefits on “climate, public health, energy efficiency, and food security.”

Montreal Protocol

The Montreal Protocol is an international treaty aimed at eliminating ozone depleting substances, which are also potent greenhouse gases. The treaty’s net contribution to climate mitigation is about five to six times larger than the Kyoto Protocol’s first commitment period targets.

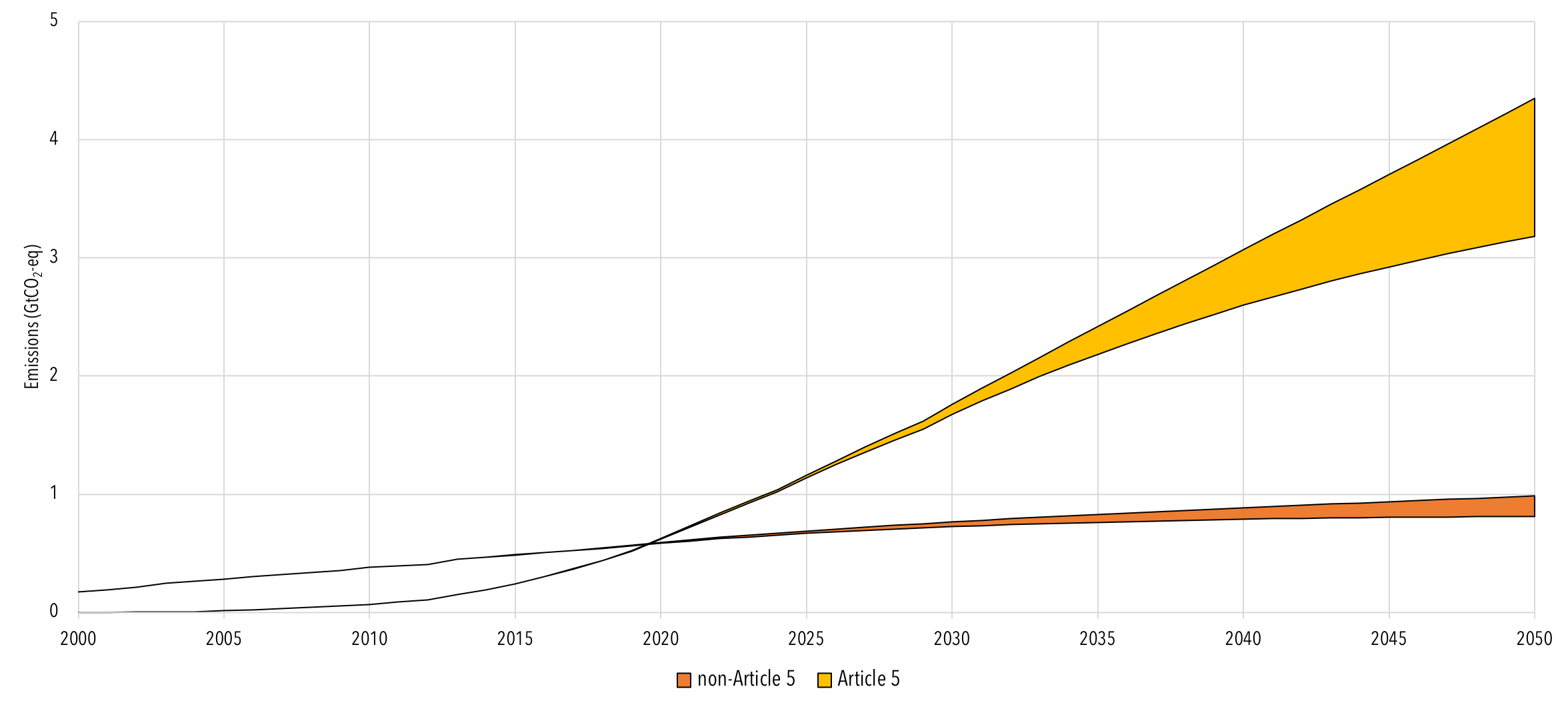

At the 2016 Meeting of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol in Kigali, Rwanda, countries around the world agreed to a legally binding commitment to reduce HFC emissions that could prevent up to 0.5 degrees Celsius of warming by 2100. This landmark agreement, known as the Kigali Amendment, includes targets and timetables to replace HFCs with cleaner alternatives, provisions that restrict countries who ratified the protocol from trading with countries who have not beginning in 2033, and a commitment by richer countries to finance poorer countries’ transition to the new standards.

U.S. Efforts

Under the Obama Administration, the U.S. EPA issued New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) to address methane emissions from new, modified and reconstructed sources in the oil and gas industry. It set emission limits for methane, covered additional sources located at oil wells and processing plants than the previous 2012 NSPS rule, and required owners and operators to check and repair leaks. In August, 2020, the EPA rescinded portions of the standards relating to transmission and storage of fossil fuels, and removed methane-specific requirements, arguing that they are covered by the volatile organic compound standard.

IRA Methane Fee

In 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act established a for petroleum and natural gas facilities that are required to report greenhouse gas emissions under the U.S. EPA Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program. The fee applies an explicit price on methane emissions above a certain threshold. The program begins in 2024, charging $900 per metric ton of methane emitted, increasing to $1,200 in 2025, and $1,500 from 2026 on.

Voluntary Efforts

The EPA has established several voluntary programs aimed at reducing high-GWP emissions. In September 2014, the Obama administration announced a series of voluntary commitments from chemical firms, manufacturers and retailers, and the federal government to move rapidly away from HFC-134a and similar compounds and to shift to more environmentally friendly replacements.

U.S. EPA SNAP

The EPA also maintains a regulatory program called the Significant New Alternatives Policy Program (SNAP). Under this program, the EPA may evaluate and control substitutes to ozone depleting substances to ensure that they are more environmentally benign than the substances they seek to replace. In August 2014, under the SNAP Program, EPA proposed to limit the use of certain HFCs in mobile air conditioning, certain types of foams, and aerosol applications. In August 2017, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit ruled EPA lacked the authority to require manufacturers of HFCs to replace HFCs based on climate change, though those who had not made the switch yet to non-ozone depleting substances could be required to switch to those that have lower climate warming potential. In 2018, the EPA under the Trump administration threw out the modified rule, but in April 2020, the D.C. Court upheld the rule.

2020 Year-end Omnibus

In December 2020, as a part of end-of-year legislation, Congress passed a bill that will phase down HFCs by 85% by 2036, an idea supported by both environmental and industry groups. The bill, initially introduced as the American Innovation and Manufacturing Act, will also preempt states from issuing more stringent HFC regulations for five years, or for 10 years if a replacement does not emerge. It effectively aligns the U.S. with the Kigali Amendment, which was ratified by the U.S. Senate on Sept. 21, 2022.

State-Level Action

<pMany states have greenhouse gas emissions targets, and some of these include short-lived climate pollutants. A 2016, California law established the most stringent state restrictions on short-lived climate pollutants. It set goals to cut methane and hydrofluorocarbon gases by 40 percent and black carbon by 50 percent below 2013 levels by 2030. Likewise, in November 2020, Maryland finalized regulations to phase out the use of HFCs and reduce methane emissions in order to meet their state target of greenhouse gas emissions reductions of 40% below 2006 levels by 2030.

In addition, as of August 2019, California, Colorado, Wyoming, Ohio, New Mexico, and Pennsylvania have adopted or in the process of adopting regulations to control methane from oil and gas operations.