Reducing Industrial Emissions

There are many ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the industrial sector, including energy efficiency, fuel switching, combined heat and power, use of renewable energy, and the more efficient use and recycling of materials. Many industrial processes have no existing low-emission alternative and will require carbon capture and storage to reduce emissions over the long term.

HFCs

Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) — chemicals widely used in refrigeration, air conditioning, foam blowing, and other applications — are the fastest-growing greenhouse gases. With a global warming potential thousands of times greater than carbon dioxide, HFCs can have a significant impact on climate change. Given their high emissions rates and relatively short atmospheric lifetimes (compared to carbon dioxide), efforts to reduce HFC emissions in the near term will significantly reduce projected temperature increases over the coming decades.

The American Innovation and Manufacturing Act of 2020 directs EPA to implement an 85-percent phasedown of the production and consumption of regulated HFCs over a 15-year period, manage these HFCs and their substitutes, and facilitate the transition to next-generation technologies. EPA is required to issue regulations for the HFC phasedown within 270 days after enactment (by September 16, 2021).

Oil and Gas Production

Oil and gas production is the United States’ largest manmade source of methane, the second biggest driver of climate change. In the production process, methane can leak unintentionally. It also can be intentionally released or vented to the atmosphere for safety reasons at the wellhead or to reduce pressure from equipment or pipelines.

In January 2021, President Biden issued Executive Order 13990, Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science to Tackle the Climate Crisis, directing federal agencies to review actions taken in the last four years. Among many other things, the Executive Order calls on the EPA to consider suspending or revising a 2020 technical amendment to the new source performance standards (NSPS) for the oil and gas sector by September 2021. In addition, the Executive Order calls on EPA to consider proposing regulations for methane and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from existing operations in the oil and gas sector by September 2021.

In June 2021, Congress voted to repeal the 2020 methane rule under the Congressional Review Act and the resolution was signed into law by President Biden. The measure restores the more stringent 2016 methane rule.

In August 2020, EPA issued two amendments (i.e., the 2020 methane rule) that effectively rescinded the 2016 oil and gas new source performance standards (NSPS) under Section 111(b) of the Clean Air Act. These amendments removed transmission and storage segments from covered oil and gas source categories, rescinded NSPS applicable to those sources, and rescinded methane-specific requirements for the production and processing segments under Section 111(b) of the Clean Air Act. In the amendments, EPA declared that there are no emissions impacts or potential costs from removing the methane requirements for new, reconstructed, and modified sources in the production and processing segments. The EPA justified the amendments with the claim that the current methane limits are redundant with the NSPS volatile organic compounds (VOCs) requirements in the production and processing segments (e.g., fugitive emissions, pneumatic controllers, pneumatic pumps, and compressors).

Operators new oil and gas wells must now follow the 2016 methane rule, which required them to find and repair leaks and capture natural gas from the completion of hydraulically fractured oil and gas wells. They must also limit emissions from new and modified pneumatic pumps, and from several types of equipment used at natural gas transmission compressor stations, including compressors and pneumatic controllers. When it issued the rule in 2016, EPA estimated it could prevent the emission of 510,000 short tons of methane in 2025 (the equivalent of 11 million metric tons of carbon dioxide) in addition to reducing other harmful air pollutants such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs, which are ozone-forming pollutants).

Regardless of the regulatory approach, EPA continues to work with industry and states through its voluntary Natural Gas STAR program to reduce methane from existing oil and gas operations.

In addition, Executive Order 13990 would require the Department of Interior to review a 2018 rule that rescinded the 2016 methane emissions rule from wells on lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Indian lands. The 2016 rule placed the first limits on flaring natural gas and increased disclosure requirements. Furthermore, it prohibited venting except in specified circumstances, required pre-drill planning for leak reduction, and increased use of leak-detection technology.

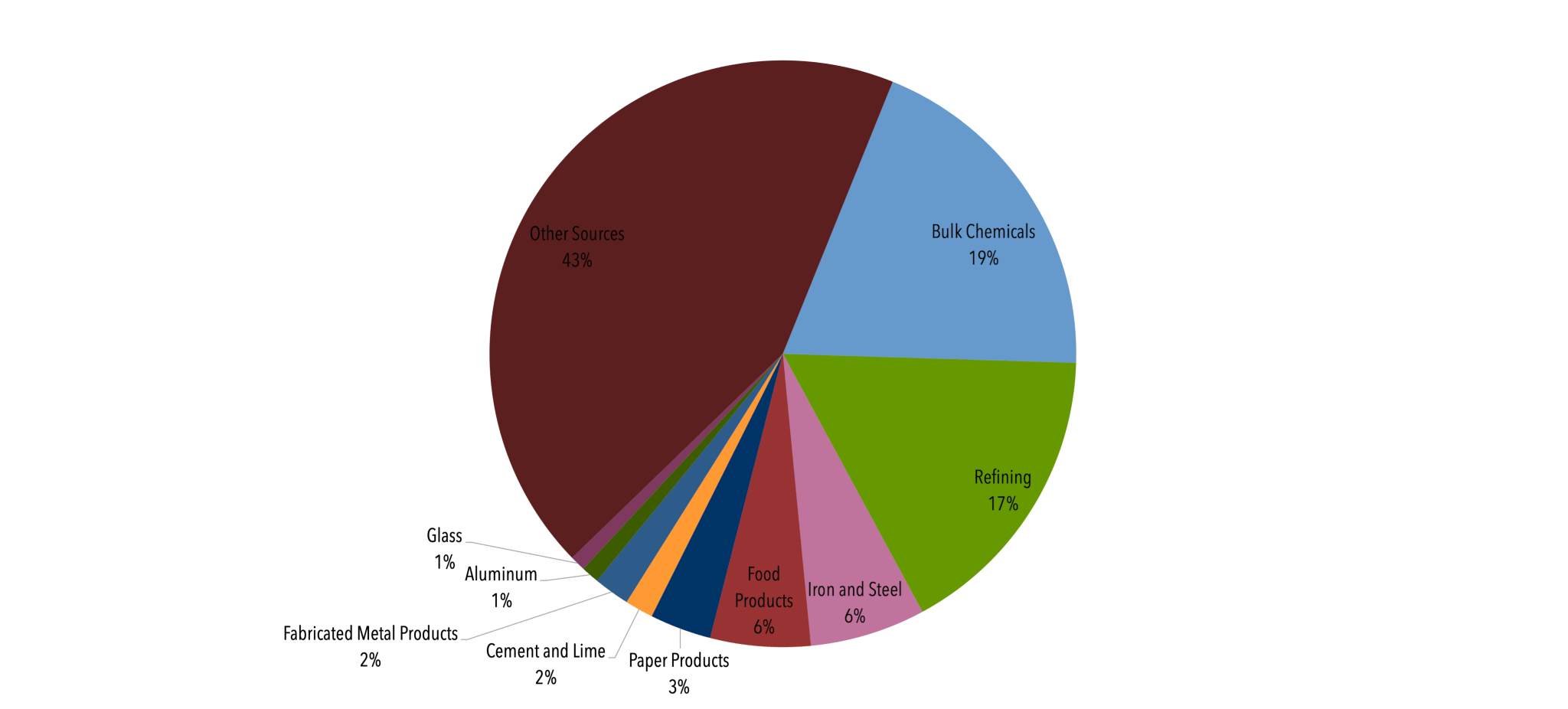

Other Industrial Sources

Other industrial sectors, such as refineries and cement kilns, have been regulated for certain pollutants, including particulate matter (PM), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and dioxides of nitrogen (NOx), since the Clean Air Act became law in 1970.

Section 111 of the act requires the regulation of pollution from new, modified, and reconstructed facilities through the New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) program. NSPS are technology-based standards that apply to specific categories of stationary sources. NSPS for pollutants are regularly strengthened by EPA to safeguard human health and the environment as technology advances and new pollution controls become more economically feasible. The Clean Air Act requires EPA to establish New Source Performance Standards for greenhouse gas emissions from all significant emitting subsectors, as clarified in the U.S. Supreme Court case Massachusetts v. EPA.