Scientists have typically been cautious when discussing the link between a single extreme weather event and climate change, preferring to focus on broader trends. Previous work, including a paper I wrote with Jay Gulledge four years ago, described a framework for how to think about the link.

But a new report from the National Academies of Sciences (NAS) is making the connection more clear by defining the relative contributions of climate change and other natural sources to the risk of individual weather events. The NAS report – an exhaustive, systematic examination of the peer-reviewed literature – finds high confidence in attribution studies linking individual extreme heat and cold events and climate change, and a more moderate confidence level for several other types of events.

Climate change is making extreme weather more likely. But individual weather events like heat waves or hurricanes are always the product of several risk factors, such as El Nino, climate change or other natural variability, akin to how a poor diet and smoking increase the risk of poor health later in life.

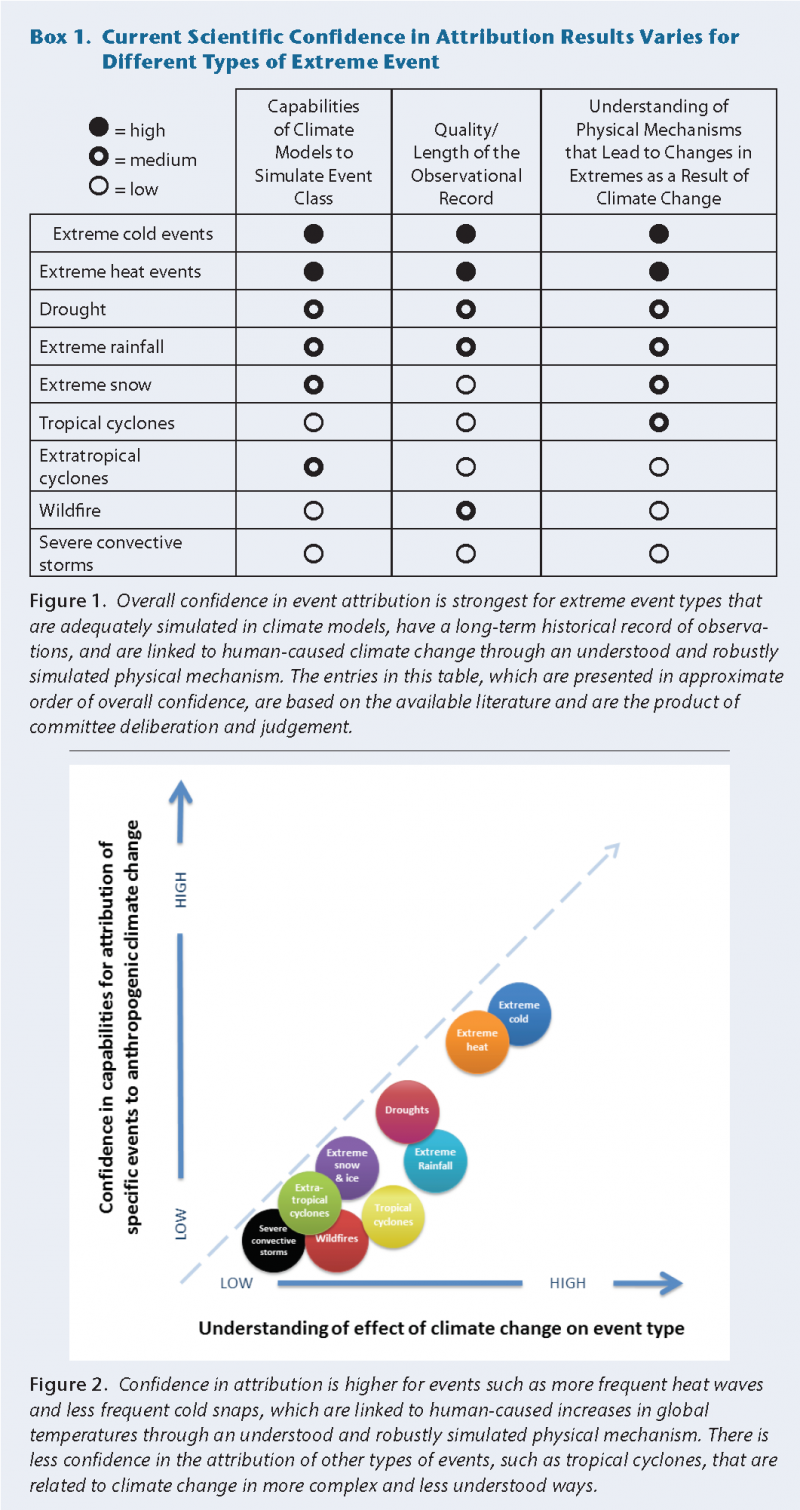

Extreme event attribution attempts to quantify the influence of climate change in comparison to other factors. Determining to what extent climate change strengthened or weakened the event can further our understanding of how much impact climate change is having on our weather.The NAS report assigns a confidence level to the climate impact for a variety of weather events based on three supporting lines of evidence:

- The physical mechanisms that link climate change to a particular extreme

- The length and quality of the observational record showing the baseline risk level and changes to date

- Computational climate modeling showing an increase in risk for a class of extreme event

The report finds the strongest links to climate change for extreme heat and cold, with the highest level of confidence across all three lines of evidence. Drought and extreme rainfall have medium confidence for physical understanding, observation and modeling. Extreme snowfall has medium conference for two out of three, physical understanding and modeling, while the observational record for snowfall is poor.

At the lower end of the scale, tropical cyclones, extratropical cyclones, and wildfire all have moderate confidence in at least one category, while severe thunderstorms have low confidence across the board.

Ongoing improvements in modeling, observational techniques and theory have improved these results over time and further research will continue to refine them. Policymakers and disaster response planners who use past and current events as a guide to assess vulnerabilities to extreme weather now can be further informed by how future risk is likely to change. This will allow us to better prioritize our investments in prevention and adaptation.

Understanding extreme weather risk is critically important work as improved climate adaptation and preparedness can save lives, regardless of how closely an event is linked to climate change.

Dan Huber is a former science and policy fellow at the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. He is now an environmental analyst at the New York City Independent Budget Office.