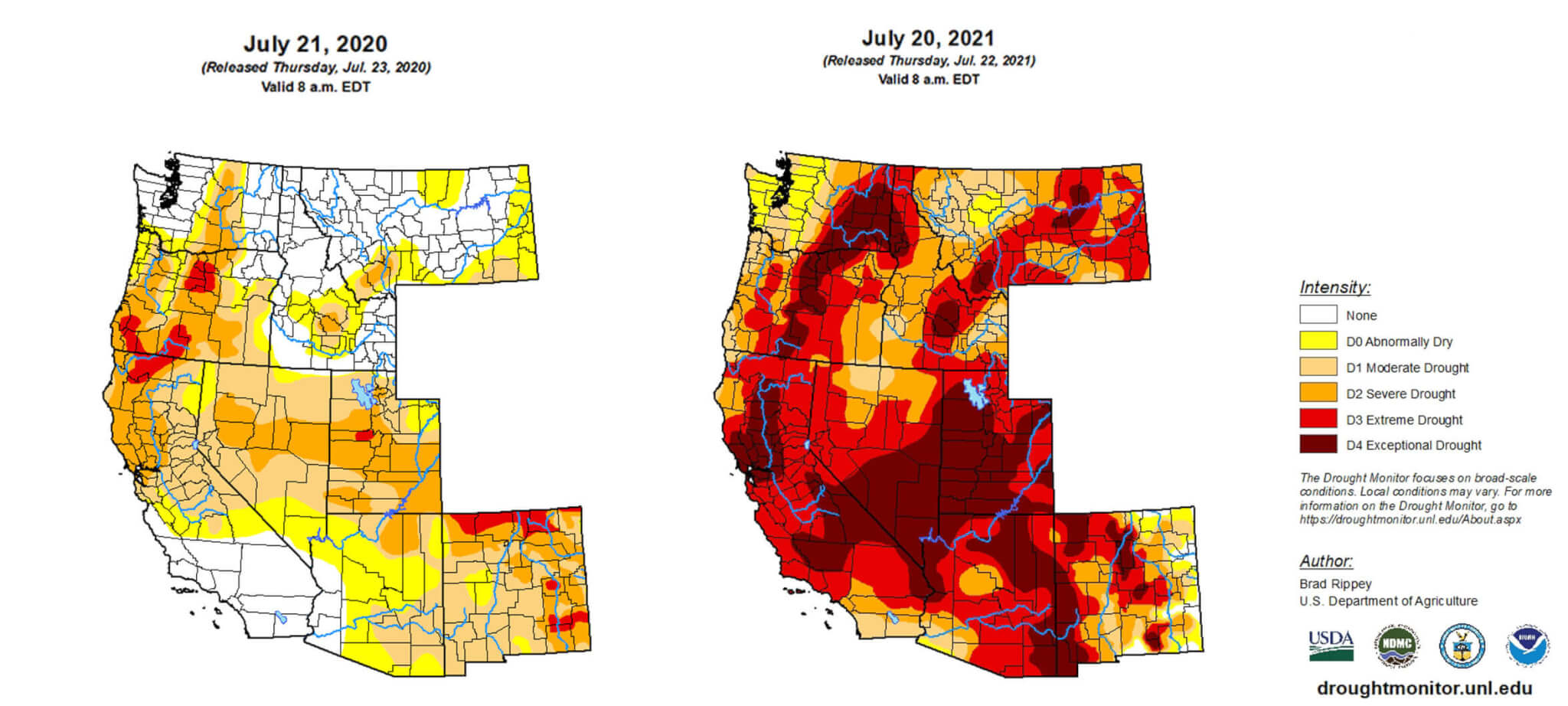

Western states have dealt with drought for decades, and in fact, the region is now in its 21st year of what scientists call a “megadrought.” But this year’s drought conditions are unusual because they are so widespread and intensifying so rapidly. Scientists raised strong concerns over hotter-than-average spring temperatures and low soil moisture, strong predictors of an intense drought season. Now, unfortunately, their predictions are coming true.

The drought has several causes. In the past decade, Western states have experienced less precipitation overall, and warmer temperatures, leading to higher evaporation rates and less precipitation falling as snow. These impacts have drastically decreased stored and available water. Moving forward, climate change is projected to continue reducing Western snowpack and increase the likelihood of chronic, long-duration drought, without further greenhouse gas mitigation and water management actions.

Extreme heat this summer has exacerbated the drought, further diminishing river flows, increasing evaporation from reservoirs, and drying soils and vegetation. A June heat wave set record-high daily temperatures across western states. Across the region, high temperatures over 100 degrees F lasted for days; in Phoenix, the temperature hit 115 degrees for six consecutive days. The usually moderate Pacific Northwest and Western Canada shattered heat records by more than 5 degrees in some places. Nationwide, the last week of the hottest June on record broke 1,238 daily maximum temperature and 1,503 daily minimum temperature records.

Recent research suggests that the West is becoming increasingly dry. Working in tandem with heat, arid conditions have already contributed to wildfires, which are likely to continue as the summer progresses. Forecasters believe this year’s wildfires could rival 2020’s fires — which burned an area equal to the size of Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island combined — leaving an estimated $16.6 billion in damages.

In addition to increasing wildfire risk, drought conditions are already having wide-reaching impacts on communities, agricultural operations, and electricity infrastructure. Rural communities are seeing their wells dry up and break down, limiting access and increasing costs for household water usage, an issue particularly pressing for communities with majority low-income, migrant residents. Some western towns are even putting a pause on construction of new homes to limit population growth as they try to tap new water sources.

High temperatures and dry soils are also affecting agricultural production and making conditions dangerous for workers. Crop yields could be down by over 75 percent this year, and soaring animal feed costs as well as dried-out grazing pastures are forcing some ranchers to sell off livestock. Impacts like these are threatening our nation’s food production and the livelihoods of farmers and agricultural workers.

Hydroelectric power generation is currently limited by low water levels in the Colorado River, and electric utilities may plan power outages in the driest (and often hottest) conditions later this summer to reduce the risk of equipment sparking wildfires in areas with dried-out vegetation. These impacts not only threaten the physical health and well-being of people who live in these areas, but local economies as well.

To reduce these impacts and prepare for future droughts, communities and regions must work to implement community-informed resilience measures locally, with support from state and federal governments. Actions that can build resilience to future droughts include: encouraging or requiring individual water conservation through local codes and ordinances; incentivizing low-water-use landscaping; incorporating drought into city planning processes; and educating the public on how and why to conserve water at the individual level. These efforts also offer co-benefits, such as reducing water bills and maintaining healthy ecosystems for local wildlife.

States and the federal government must also support drought resilience, and in recent years, federal agencies have enhanced support for resilience across hazards at the local level. For example, FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program, now in its first year, represents the federal government’s largest, sustained increase in funding for states and localities to combat drought, storm surge, sea level rise, and other hazards. Yet, as C2ES is currently exploring, the federal government could do much more to help accelerate community and regional resilience. It can do this by providing financial and technical resources in a robust, equitable, and coordinated way, and by acting as a supportive partner to state, local, and tribal leaders planning for and investing in resilience. An upcoming C2ES policy brief will include our recommendations for federal actions to advance resilience on the ground.

Drought conditions in 2021 have left the West with the driest, most dangerous conditions in decades, threatening water supplies that support millions of lives and livelihoods. Climate change is likely to make these conditions even worse, creating an urgent need for resilience measures. While cities and states can enact drought resilience measures, they work much better with federal support and coordination. While federal resources like pre-disaster hazard mitigation funding and planning support won’t address the immediate drought crisis at hand, they will help communities put resilience measures into place and better prepare residents and businesses for future extreme droughts events.