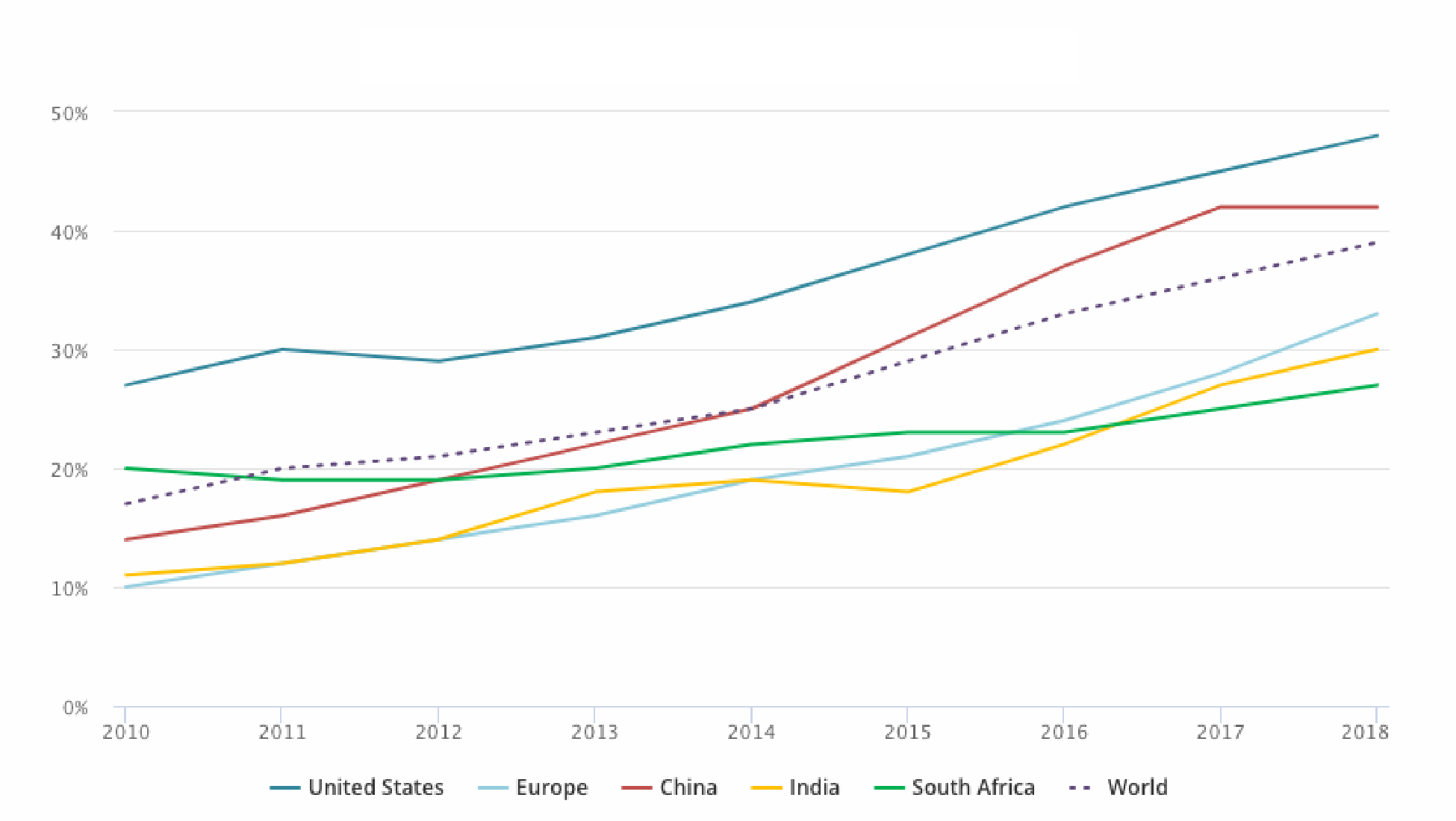

On almost any televised football game, the majority of automobile ads are for SUVs and pickups, so automakers are still trying to cash in on the boom, which now pervades through major economies like India and China, and other developing nations as well. In countries like China, SUVs are considered status symbols of wealth, and as other developing nations grow their middle classes, demand for SUVs is expected to be strong.

All this is bad news for emissions. The same IEA report noted that global carbon dioxide emissions rose 1.7 percent last year, and U.S. transportation emissions have risen every year since 2012; the sector became the economy’s top emitter in 2016.

A lead author of this month’s report, Tim Gould, told the audience at the release event that the growth of SUVs has been one of the “biggest elements behind the recent rise in emissions.”

Meanwhile, car dealers are selling fewer compacts and economy cars, and few are selling electric vehicles (EVs) at all. A recent study by the Sierra Club found that 74 percent of dealerships surveyed nationwide had no EVs for sale. The study also found dealership staff were not equipped with knowledge on local and federal incentives, and oftentimes EVs were not adequately charged for a test drive. A spokesman for the National Automobile Dealers Association told Automotive News that the number of EVs stocked on car lots is simply a function of supply and demand.

Emissions reduction efforts would suffer if SUV market share continues at its current pace. The IEA report says if worldwide consumer demand for SUVs continues to grow at the rate it has in the past decade, SUVs would add nearly 2 million barrels a day in global oil demand by 2040. The IEA estimates that’s enough oil to offset the savings from nearly 150 million electric cars.

The report also found that electrifying 40 percent of SUVs and the same amount of small and medium cars by 2040 would send oil global demand from vehicles plummeting from today’s level by 14 million barrels per day.

It’s also important to note that all vehicles designated as SUVs are not the same. Many of the newer crossovers offer better gas mileage than some sedans. And while automakers are preparing to roll out some all-electric models, they are also keeping up with demand for more truck-like vehicles that have room for families and their belongings.

But electric SUVs so far are more expensive than their gasoline counterparts. Rivian’s all-electric R1S will be priced to compete with the Cadillac Escalade and other high-end gasoline powered SUVs at $72,500. However, it won’t be released until 2021. A currently available electric SUV, Tesla’s Model X, retails a little more expensive, at $81,000.

In the same time that transportation emissions have grown, the United States has made great headway in reducing power generation emissions. It would be a shame if our own transportation habits get in the way of bringing emissions to net zero.

What can be done? For one thing, we need a federal greenhouse gas performance standard, coordinated with states, ensuring at least half of new light-duty vehicle sales are zero-emission vehicles by 2035, and a similarly ambitious standard for medium- and heavy-duty trucks. Congress should also extend the current electric vehicle tax credit, make it available as a point-of-sale rebate, and expand it to include all new zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs), including fuel cell electric vehicles and medium- and heavy-duty trucks.

On the state level, we need to develop comprehensive long-range plans to speed up the deployment of ZEV charging and refueling infrastructure. Congress can help by funding development of these state plans along with a variety of financial tools, from grants to low interest financing, in states that have plans to construct charging and refueling infrastructure.

Local governments also need dedicated federal planning support, which they should use to develop integrated transportation and land use plans that expand non-automotive transportation options.

These recommendations will give automakers more incentive to electrify their vehicles, help EVs in general become more affordable, and encourage investment in charging stations and infrastructure needed to make EVs a greater part of our everyday transportation. With more zero-emitting vehicles of all sizes on the road, transportation emissions will start moving in the right direction, and push overall emissions closer to the level needed to avoid the worst climate impacts.

If we implement these recommendations, when my friend is looking to replace his gasoline SUV around 2035, he’ll have plenty of affordable, all-electric models to choose from.

Updated January 2020: Aston Martin’s electric SUV is not expected to be offered until 2022.