Publication

Carbon Pricing Proposals in the 119th Congress

Placing a price on carbon provides a market-based solution to […]

Pennsylvania is taking steps to become the first major fossil fuel producing state to join the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, the Northeast’s regional cap-and-trade program for power generators.

The state has made progress in reducing emissions in recent years, but Gov. Tom Wolf’s executive order instructing the Department of Environmental Protection to make a plan to join RGGI demonstrates a major commitment to quickly reducing emissions from the state with the fifth-highest power sector emissions in the nation (more than all RGGI states combined).

Pennsylvania is not only the second-largest natural gas producing state, but also the third-largest coal producer, which makes it the second-largest total energy producer in the United States. If it were a separate country, Pennsylvania would be the world’s fourth-largest producer of gas and 14th largest coal producer.

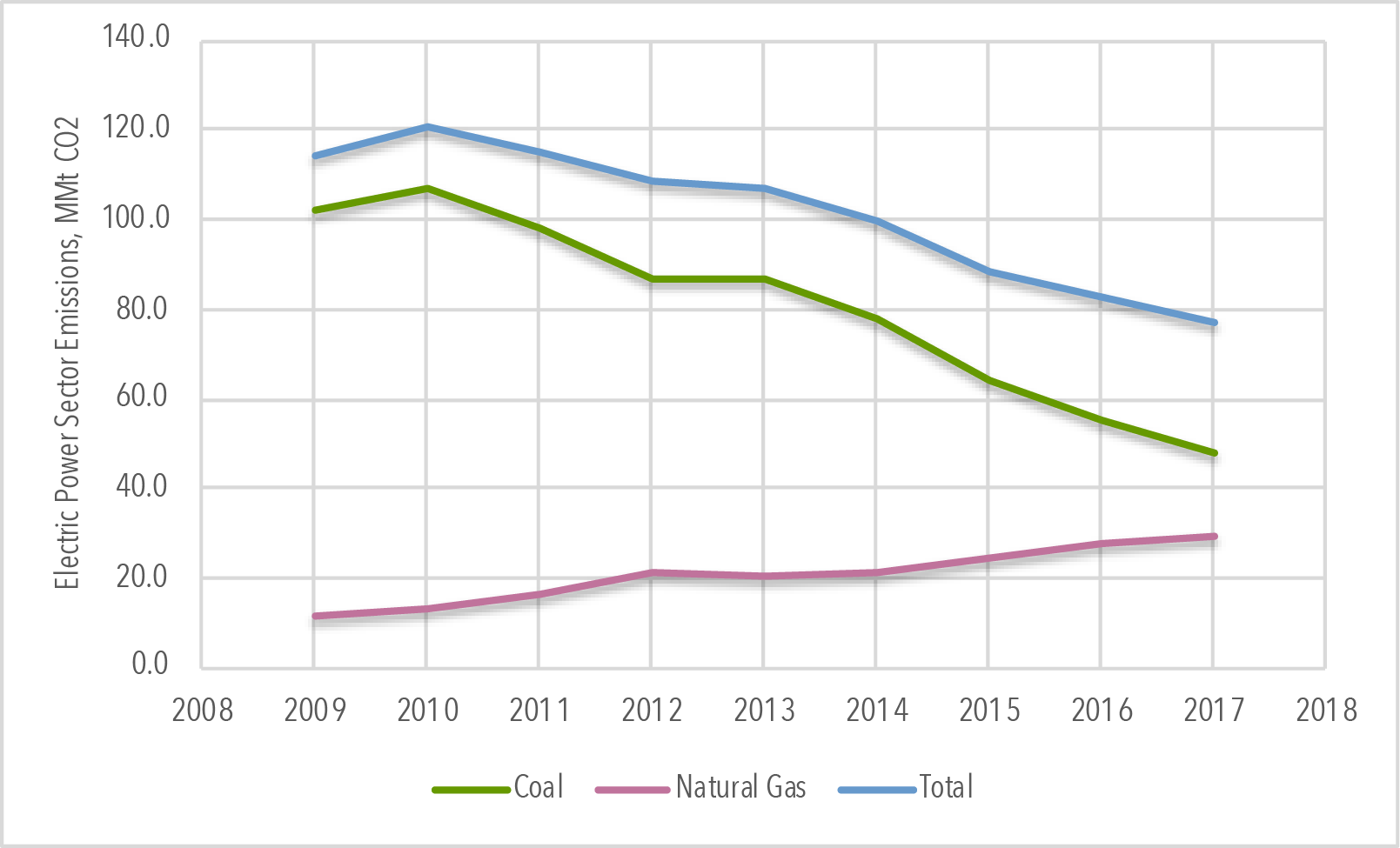

Pennsylvania’s power emissions have dropped by 32 percent in the last few years, mainly because power generators have largely switched the primary fuel they use to generate electricity from coal to natural gas. Consequently, emissions from the state’s natural gas power plants increased by more than 150 percent from 2009 to 2017.

While carbon-free nuclear power represents 34 percent of the electricity generated in Pennsylvania, the state’s nuclear power stations have been struggling to compete against abundant, cheap natural gas. Participating in RGGI could help prevent the premature closure of the state’s nuclear reactors. Putting a price on carbon emissions would eventually play a role in preserving low- or non-emitting nuclear sources or even developing new capacities to meet GHG reduction goals. Reducing emissions and improving air quality are not only important for combating climate change, but they also have public health benefits (e.g. avoided premature deaths, heart attacks, hospitalizations, and emergency room visits). These benefits were estimated at $5.7 billion in the RGGI states from 2009 to 2014.

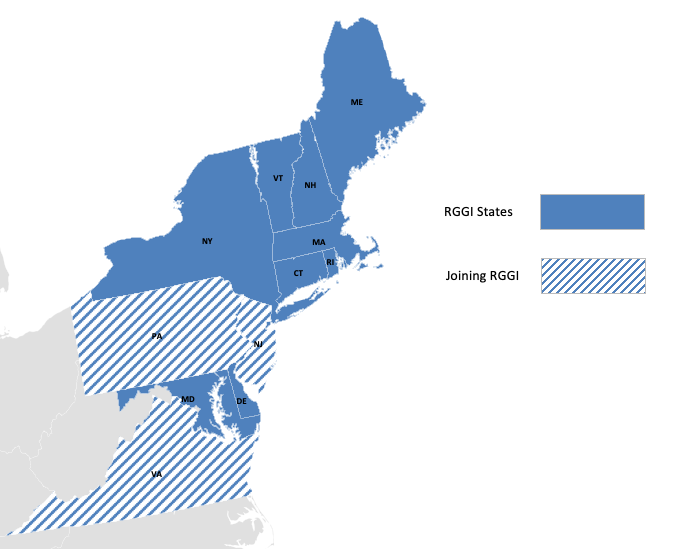

Established in 2005, RGGI is a cooperative effort among the states of Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont to cap and reduce carbon dioxide emissions from the power sector. Within the RGGI states, all fossil fuel power plants with a capacity over 25 megawatts (MW) are required to obtain allowances equal to their carbon dioxide emissions .

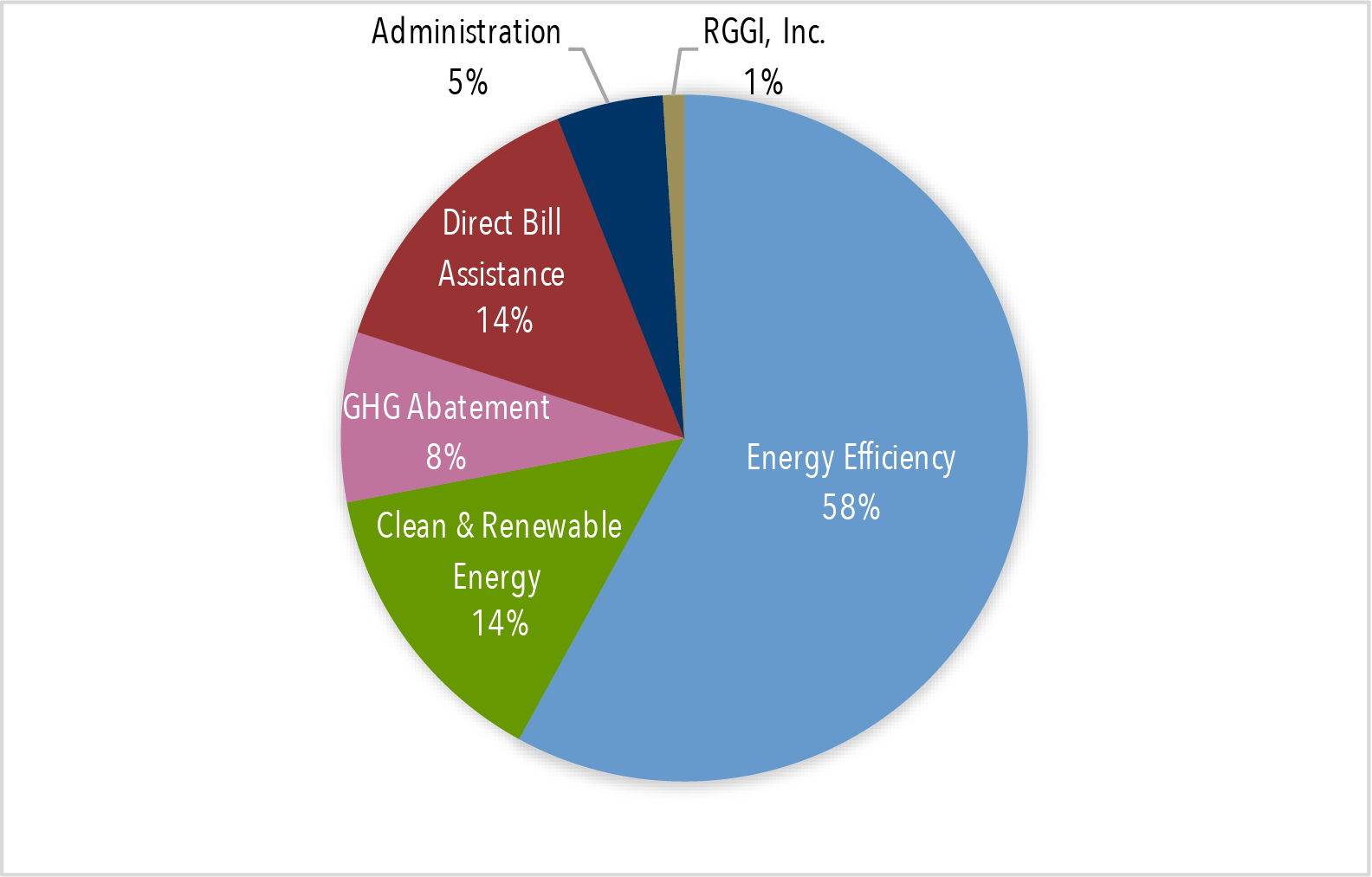

Since RGGI went live in 2009, the annual average carbon dioxide emissions from the power sector decreased by 40 percent, while emissions in non-RGGI states and California (which also has a cap-and-trade program) decreased by 18 percent. Meanwhile, the RGGI states’ gross domestic product (GDP) continued to grow, outpacing economic growth in most states that do not have a price on carbon. Additionally, RGGI states have accumulated more than $3.2 billion in revenue from auction proceeds, money that has been invested in energy efficiency, clean and renewable energy, greenhouse gas abatement, and direct bill assistance.

RGGI emissions reductions can be attributed to several factors, including the post-2008 recession, complementary environmental programs (e.g. renewable portfolio standards), and low natural gas prices. It is challenging to assess the effect of each factor on the emissions reductions in the region, however, a study from Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Solutions found a significant impact. The study found that “after the introduction of RGGI in 2009, the region’s emissions would have been 24% higher without the program, accounting for about half of the region’s emissions reductions during that time, which were far greater than those achieved in the rest of the United States.”

In 2017, RGGI announced program changes that reduce its emissions cap 30 percent by 2030, relative to 2020 levels. In order for states to join RGGI, they must set an emissions cap that is consistent in stringency to that established in the RGGI states. For Pennsylvania, this could be translated into bringing up to $6.6 billion of auction proceeds between 2020 and 2030. New Jersey and Virginia (which are also expected to join RGGI) could also bring up to $1.4 billion and $2.3 billion respectively.

According to Wolf’s executive order, Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) should develop a regulation that will cut carbon pollution from power plants and enable the state to participate in RGGI. The DEP must submit its proposal to the state’s Environmental Quality Board by July 31st, 2020. However, the legislature could potentially delay the process—similar to what happened while drafting regulations to fulfill the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan—by proposing legislation with new rules to limit how Pennsylvania can participate in RGGI.

As Pennsylvania and the other new members join RGGI, policy coordination will be important in cutting emissions leakage in the Northeast. This happens when power generation, especially from coal, is diverted from RGGI states to the surrounding non-RGGI states.

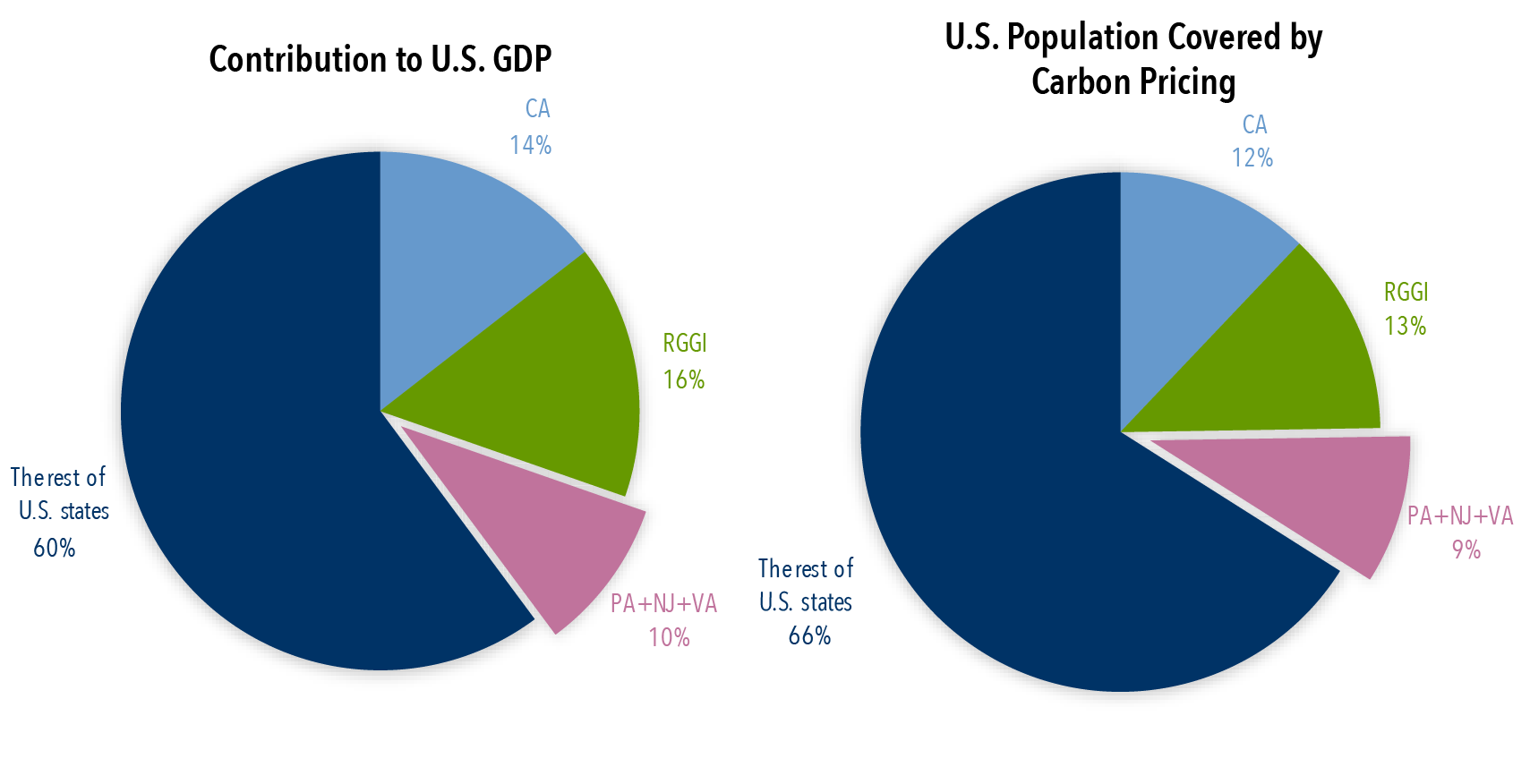

The anticipated expansion of RGGI would also tap into state efforts to combat climate change, even in the absence of federal action. This would increase the share of U.S. GDP that is covered by carbon pricing as well as the percentage of the U.S. population living in a state with a price on carbon. Because Pennsylvania is the largest net exporter of electricity in the United States, this would help power-importing states to achieve their own clean electricity targets.

New Jersey will rejoin RGGI in 2020, and Virginia is expected to join in 2021. When these two states and Pennsylvania are on board, carbon pricing policy will cover 40 percent of the U.S. economy and more than a third of the population.

As more states join forces to reduce emissions, they offer a great opportunity to combat climate change through an approach similar to the bottom-up elements of the of the Paris Agreement. As a major fossil fuel producer, Pennsylvania has an opportunity to join other leading states who have shown that it is possible to couple economic growth and emissions reductions.