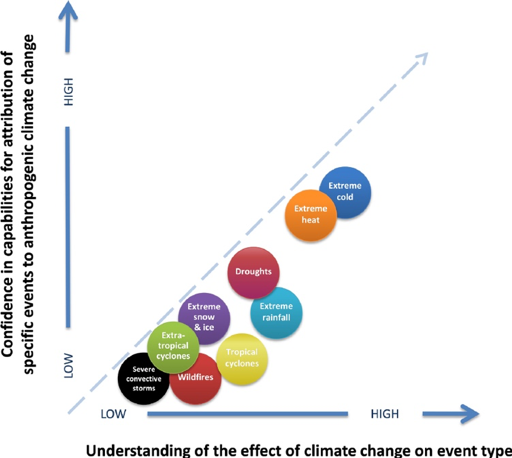

While there have been many advances in the greater science of event attribution, it’s really tricky for tornadoes.

First, tornado records are relatively limited. Records only go back to the 1950s, and tornadoes are mainly measured only after people observe them or their physical damage. Most of the increase in tornadoes across historic records is likely related to improved radar and increased reporting (a result of larger populations in areas affected by tornadoes) rather than to a growing occurrence (which may also be happening). This means we don’t have a longer-term sense of what “regular” patterns or behavior of tornadoes are, making it hard to isolate and identify changes.

Secondly, tornadoes are very geographically limited and also are relatively brief events when compared to droughts and hurricanes, while climate models are very coarse, averaging climate conditions over larger areas. That makes it difficult to simulate tornadoes specifically.

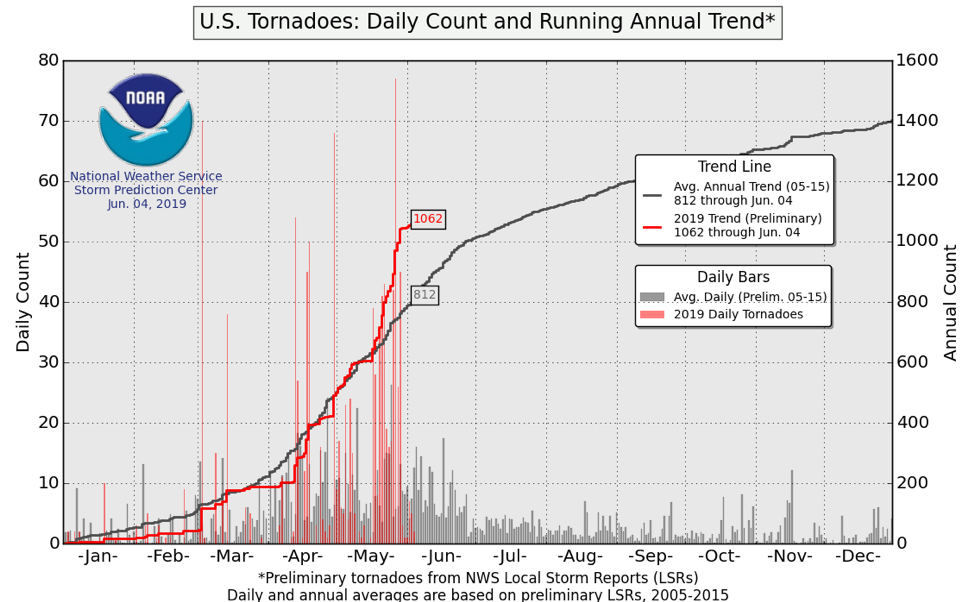

While they’re still hard to directly link to climate change, we have seen some tornado trends:

- The U.S. is seeing a greater frequency of tornadoes, but they’re occurring on fewer calendar days.

- Tornado seasons are increasingly variable and starting earlier in the year in some places.

The conditions were right for the series of tornadoes in May because of the jet stream. Inconsistencies in jet stream patterns create extreme weather conditions across the country, with some places experiencing above average heat while others experience flooding and still others experience abnormally cool temperatures. Some scientists think that the abnormalities in the jet stream could be related to reduced Arctic sea ice and warmer temperatures in Alaska, effects potentially linked to climate change.

As scientists seek to better understand how climate change affects tornadoes, they are looking at conditions that could create “severe convective storms” including any storms that produce strong winds, hail, tornadoes, lightning, or heavy precipitation. Unusually warm, humid air conditions in the lower atmosphere and cooler-than-usual conditions in the upper atmosphere can create strong updrafts and down drafts. Vertical wind shear turns that energy into convective storms. A warming climate could increase the likelihood of certain conditions but not all of them, making the outcome for tornadoes very difficult to predict. Scientists are working to model these environmental variables.

Despite the progress in attribution science in recent years, we still have a long way to go with events that are affected by more complex factors than just heat or moisture. But this uncertainty in the link between climate change and tornadoes should not obstruct community decision making. Stronger building codes that prepare buildings and improved early warning systems and evacuation procedures can help communities better prepare for tornadoes as well as for confirmed climate impacts like flooding and wildfire.