The polar vortex that afflicted 50 million people in the Midwest and Northeast with an extreme chill last week may have struck many (including President Trump) as entirely at odds with the concept of global warming.

But cold spells like this are not unexpected by climatologists. In fact, more extreme weather – more often hotter, but sometimes colder – is among the major risks projected as global temperatures rise. Indeed, just a week later, we saw temperatures rise to 20-plus degrees above the seasonal average in parts of the eastern United States, with Washington, D.C., experiencing a record high on Feb. 5.

Here’s why extreme cold is consistent with global warming.

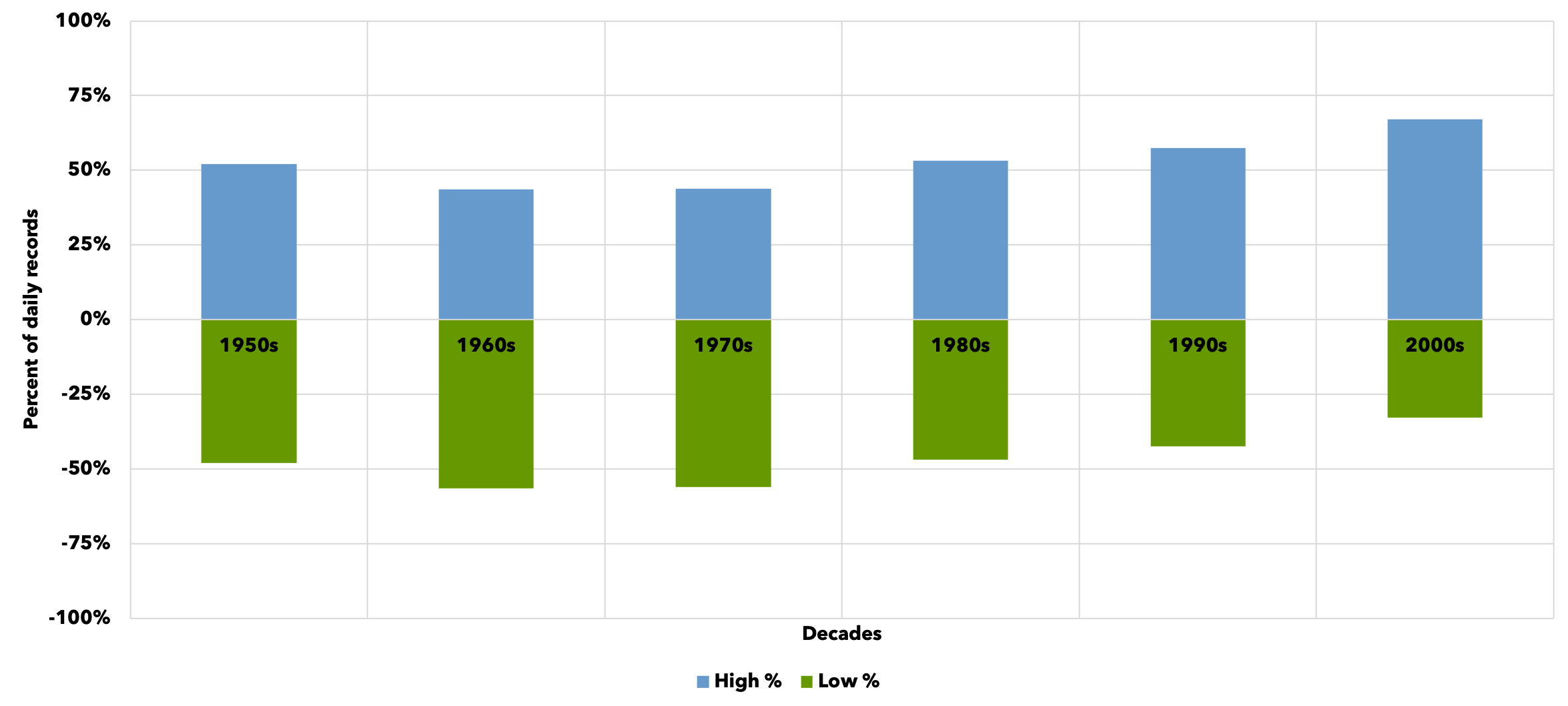

To begin with, the world is hotter than it was 100 years ago (or 50 years ago, or 20 years ago). Globally, January was more than 0.4 degrees C (0.7 degrees F) warmer than the 1981-2010 average and the fourth warmest January on record. Within the United States, while the Midwest saw record lows, the Pacific Northwest saw record daily highs. These warmer averages all followed 2018, the fourth hottest year on record (behind 2015, 2016 and 2017) and every year since 1977 has been warmer than the 20th century average.