With Hurricane Florence making landfall on the Southeast coast of the United States, Typhoon Mangkhut threatening devastation in the Phillipines, and Hawaii experiencing its unprecedented third hurricane this season, it’s a sensible time to look at the way coastal communities can better plan for storms of this type and build resilience to their impacts.

Forecasters are predicting a large storm surge, inland flooding, high winds, and heavy rain from Florence and similar conditions from Mangkhut on the opposite side of the world. While, of course, the immediate attention is on disaster response and recovery, how these coastal areas bounce back from these severe storm impacts is related to how they invested in resilience strategies like sea walls, levees, beach restoration, wetlands, and building elevation. Other coastal communities can take these powerful storms as a call to action, and increase their resilience before the next “Big One” arrives.

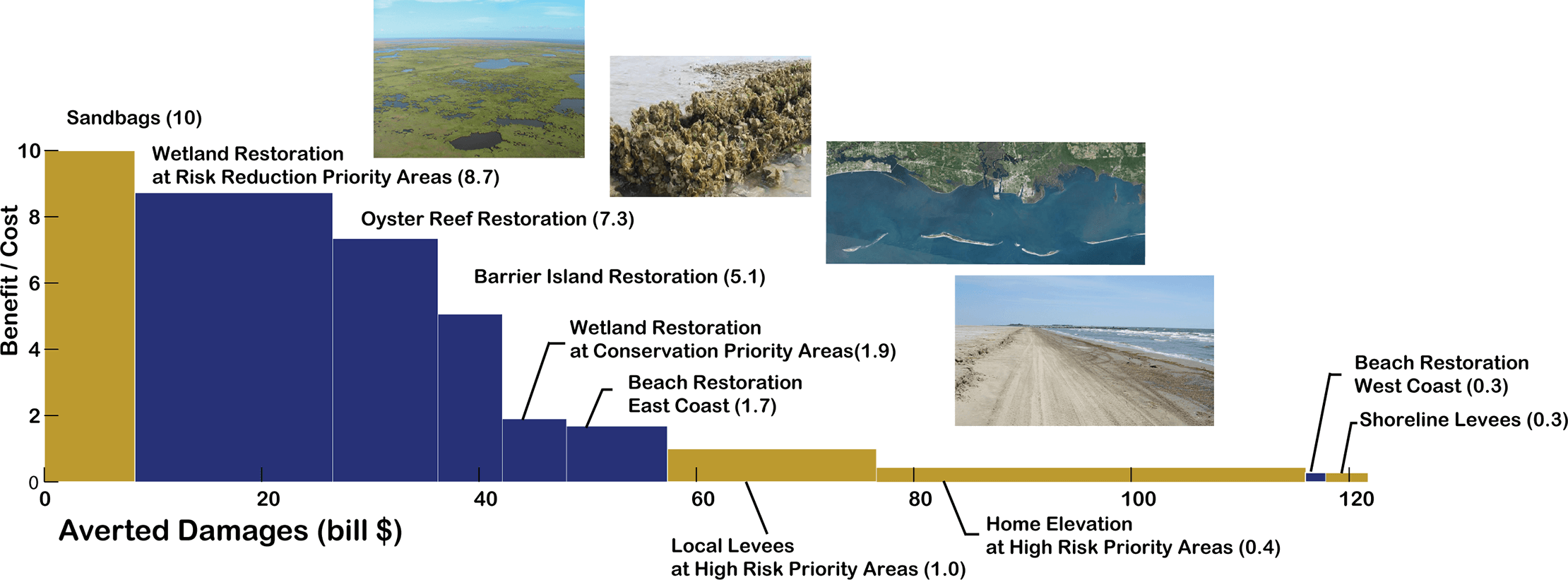

The strategies many communities employ to increase coastal resilience – like strengthening or elevating buildings, restoring ecosystems like wetlands or oyster reefs, or even limiting coastal development – are known to save money in the long run by avoiding storm losses. But how can the most cost-effective strategies with the greatest benefits be identified and employed?

Coastal communities have a long history of responding to hurricanes and addressing their aftermath, but climate change is making this task harder. Warmer oceans make these storms stronger, and rising seas make the storm surge they create even greater (not to mention the nuisance flooding that happens even on sunny days).

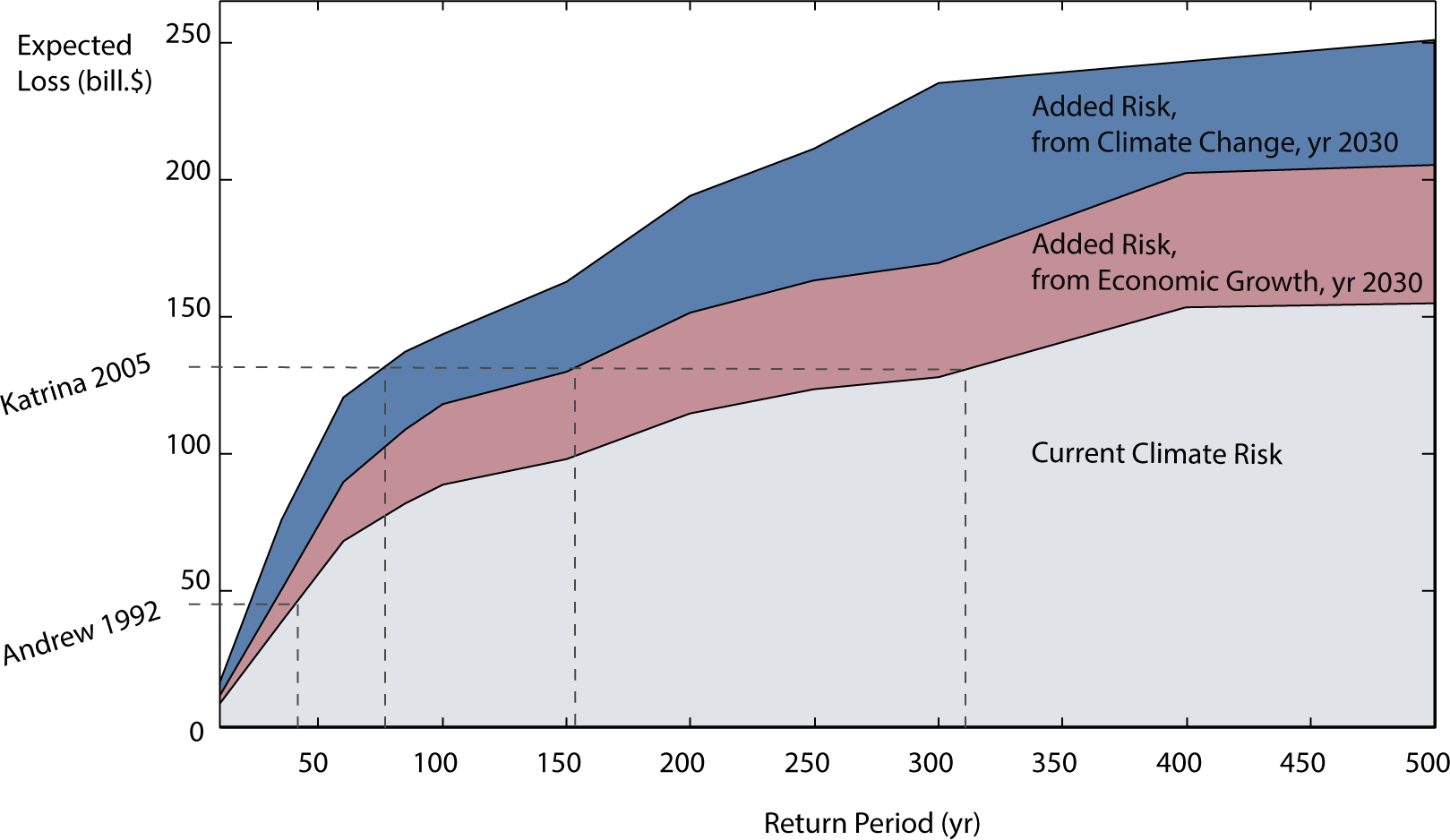

Climate change complicates the way communities evaluate the cost-effectiveness of actions to reduce the impact of hurricanes, because it increases the likelihood that a certain amount of damage will occur – meaning “100-year storms” may reoccur more often than they did in the past.

But new analytical frameworks accounting for those effects can help identify not only the economic benefits of resilience but also include risk from increased future development (because more property on the coast means growing potential for property damage) and how those costs and benefits stack up for communities up and down the coast.

A recent study from researchers at the University of California Santa Cruz, the Nature Conservancy, and ETH Zurich, used an open-source, probabilistic tool and the economics of climate adaptation (ECA) approach to offer an example of this type of planning. First, researchers estimated how climate change and coastal development increase the likelihood of storm damage along the Gulf Coast. They found, for example, that climate change and development by 2030 will make economic losses like those from Hurricane Katrina two to three times more likely to occur. In other words, the chance of a storm causing $131 billion in damages, as Katrina did, is two to three times more likely than it used to be. This is due in about equal parts to increased coastal development putting more structures at risk and climate change intensifying the strength and impacts of hurricanes.